The Full Story

Ludwig Bamberger was born in 1893 in Lichtenfels, Germany, in the state of Bavaria. He was educated in Germany and in 1911, at age 19, was sent to England for business training. After three years in London, he returned to Germany and served in World War I, receiving the Iron Cross second class for valor in 1918.

Ludwig joined his brother Otto and cousin Alfred in the family business, D.B.L. (David Bamberger, Lichtenfels). The company imported raw materials for the basket industry, including raffia and cane, and manufactured a variety of baskets and carpet beaters. These handmade items were shipped to shops around the world. The Bambergers also designed and manufactured educational wooden toys, many of which were specially made for Montessori and Froebel schools.

In 1922, Ludwig married Thea Spier.  Thea was born in 1898 in Frankfurt, Germany, the youngest of three children. Her father, Simon, started a shoe factory which made ladies fine quality leather boots. The family was well-to-do and had a beautiful home. Thea’s brother, Selmar, trained to become a lawyer, and her sister, Flora, went to medical school in Heidelburg. Thea was interested in music, studied piano and took voice lessons and eventually sang at the opera in Frankfurt.

Thea was born in 1898 in Frankfurt, Germany, the youngest of three children. Her father, Simon, started a shoe factory which made ladies fine quality leather boots. The family was well-to-do and had a beautiful home. Thea’s brother, Selmar, trained to become a lawyer, and her sister, Flora, went to medical school in Heidelburg. Thea was interested in music, studied piano and took voice lessons and eventually sang at the opera in Frankfurt.

The Spier family and the Bambergers were friends, and Ludwig often hiked with Selmar. Philip  Bamberger, Ludwig’s father, was very taken by Thea. Once, when visiting the Spiers, he pulled out a photo of his four sons and handed it to Thea, who was 15 at the time. He asked her, “Which one do you like?” She and Flora ran up to their room with the photo, giggling at the thought that they would consider marrying one of these boys. Later, Thea met Ludwig through Selmar. He was attracted to her and though she was intent on her music, he persuaded her to become engaged. They were married in 1922.

Bamberger, Ludwig’s father, was very taken by Thea. Once, when visiting the Spiers, he pulled out a photo of his four sons and handed it to Thea, who was 15 at the time. He asked her, “Which one do you like?” She and Flora ran up to their room with the photo, giggling at the thought that they would consider marrying one of these boys. Later, Thea met Ludwig through Selmar. He was attracted to her and though she was intent on her music, he persuaded her to become engaged. They were married in 1922.

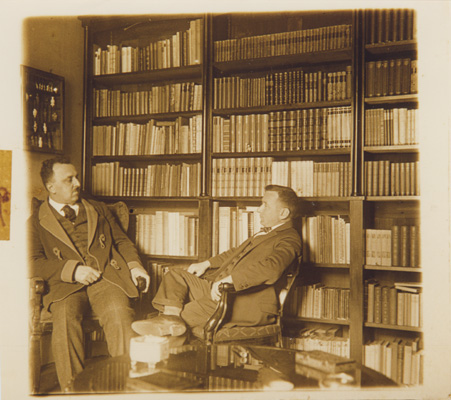

Ludwig and Thea had two daughters, Anna, born in 1923, and Eva, born in 1927. They lived in a large house in Lichtenfels at 44 Bamberger Strasse, and they employed several servants—a cook, an upstairs maid, a nanny for the children, and two gardeners. They filled their home with fine furniture and beautiful carpets, as well as avant garde art. Ludwig was an avid art collector, specializing in German expressionist  graphics and paintings. He also had a world-class library, as noted by an inventory the Nazis made when they looted the Bambergers’ home after Kristallnacht in November 1938. Only 445 books, a mere fraction of the total, were saved. The Lichtenfels town archive retains a catalog of these books, which lists the titles from Ludwig’s library.

graphics and paintings. He also had a world-class library, as noted by an inventory the Nazis made when they looted the Bambergers’ home after Kristallnacht in November 1938. Only 445 books, a mere fraction of the total, were saved. The Lichtenfels town archive retains a catalog of these books, which lists the titles from Ludwig’s library.

Ludwig and Thea left Germany and traveled to the United States in September 1938 to visit their Bamberger relatives and Thea’s cousins. They had applied for immigration visas to both the United States and England. While in New York, a telegram arrived notifying them of permission to immigrate to England. They sailed to London without ever returning to Germany. Entry into England was not easy, though they had the correct papers. British officials wanted them to stay on the ship all the way back to Germany, then sail back, but they insisted and somehow were able to stay in England. They had only their luggage and no money between them, as Germans were not allowed to leave the country with more than ten marks. Everything from their home, their bank account, and their business had been left in Germany and was confiscated by the Nazi government. The mayor of Lichtenfels then moved into the Bamberger house at 44 Bamberger Strasse and made their home his personal residence.

In England, Ludwig established a business partnership with Reginald Hoefkens, a manufacturer of baby items, and produced a new line of children’s toys and baby accessories. The bombing of London led to Anna and Eva being evacuated with their schools to Northhampton. Ludwig and Thea lived in London until the spring of 1940, when they were forced into the Onchan internment camp on the Isle of Man. Ludwig was taken first without any warning. Thea was rounded up several months later and interned in a women’s camp on the same island. Thirteen-year-old Eva was required to accompany her mother to the camp. Anna, at 17, was deemed too old to stay with them and was sent to the Hoefkens country house. No communication was allowed and for many months none of them knew the fate of the others.

Ludwig and Thea were released from the internment camp after nine months and they returned to Mill Hill, the London suburb where they had previously lived. Ludwig resumed business with Mr. Hoefkens and bought a house at 25 Homewood Grove in Mill Hill with a small garden, which he enjoyed tending. Thea was busy with the girls and the many tasks of running the household. There were no servants as there had been in Germany, and with the exception of a cleaning lady once a week, Thea did the housework, shopping, cooking, and other chores.

After rejoining her parents in London, Anna began studying at the Willesden College of Art and Hornsey Art School and worked in textile design while living with them in Mill Hill. In 1943, Anna was introduced to Karl Karesh, a native of Charleston, South Carolina, and member of the United States Army Air Forces, through friends of his that she met in an art museum in London. They married later that year.

After rejoining her parents in London, Anna began studying at the Willesden College of Art and Hornsey Art School and worked in textile design while living with them in Mill Hill. In 1943, Anna was introduced to Karl Karesh, a native of Charleston, South Carolina, and member of the United States Army Air Forces, through friends of his that she met in an art museum in London. They married later that year.

After the American army liberated the southern area of Germany in 1945, the Bamberger home became a military headquarters. Gerald Bamberger, a nephew of Ludwig’s, had enlisted in the army’s special intelligence unit assigned to Lichtenfels. Through his connections, he discovered some of Ludwig’s books and artwork stored in the basement of the town hall. After learning from Gerald that some of his family’s belongings had survived, Ludwig began a decade-long effort to retrieve them.

In 1946, Anna sailed to the United States with other military wives aboard the Queen Mary. Three years later Ludwig and Thea moved to Charleston,  South Carolina, to join Anna and Karl. The Bambergers lived in a beautiful historic home on the Battery for a year or two, and in 1950 bought a small house in Parkwood Estates and moved to the northwest section of Charleston.

South Carolina, to join Anna and Karl. The Bambergers lived in a beautiful historic home on the Battery for a year or two, and in 1950 bought a small house in Parkwood Estates and moved to the northwest section of Charleston.

Ludwig continued working to recover his family’s belongings in Germany. He corresponded with the Knorr Friedrich Company, which had taken over the Bamberger factory. They were able to help him locate some of his furniture that had been put in storage. After lengthy negotiations and payments in advance, Ludwig was able to have crates made and some of the furniture loaded and shipped to Charleston.

A large shipping container arrived in 1954, and the pieces were unpacked into the small house. The furniture included a Bauhaus-designed cherry and pearwood secretary and double chest, a circa 1740 German baroque burlwood secretary, four Bauhaus chairs, two armoires, a walnut bed, a walnut dining table, and two walnut chests used as sideboards. Some items  just would not fit and were reluctantly sold, but the Bambergers’ granddaughter Barbara Karesh Stender remembers admiring the furniture in the little house.

just would not fit and were reluctantly sold, but the Bambergers’ granddaughter Barbara Karesh Stender remembers admiring the furniture in the little house.

Opening the drawers of the antique secretary, the Bambergers were amazed to find some of their collection of German expressionist art, including works by Otto Muller, Eric Heickel, Otto Dix, Max Pechstein, Lyonel Feininger, Kathe Kollwitz, Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Emil Nolde, as well as the French impressionist Henri Matisse. The Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston exhibited their collection for several months, then loaned it to the Milwaukee Museum.

Anna recalled that the Nolde watercolor of fish had hung in the family’s dining room in Germany and that the Heickel oil painting of bathers around a pool had hung in her parents’ bedroom. These paintings were just a fraction of their original collection, but their return was a stunning surprise.

In Charleston, Ludwig tended the garden where he read books in the morning, to be joined by Thea in the afternoon. They often took walks together, until Ludwig’s health began to decline. In 1964, on the evening of Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, he died of heart failure at the age of 71. Thea continued to live in their house until she died in 1990 at age 92.